OUR J.J. Seabrook Testimony

Written from the perspective of Thomas Cogdell, member of the Remember Dr. Seabrook committee, as a testimony of God’s intentions to reconcile people. Selections from this story appear in the book, Preaching to a Divided Nation: A Seven-Step Model for Promoting Unity and Reconciliation, by Matthew D. Kim and Paul Hoffman.

Moving into the first AHOP location at MLK & Chicon. The author is top-left.

In late 2004, I received a somewhat mysterious email from my friend Greg Burnett. He had moved away from Austin TX where we had both attended the same church for a while, but was on my “I’m excited about something” email list. And I was excited because we had just rented our first location for a new house of prayer for the city of Austin – Austin House of Prayer.

Greg’s email read:

“God will bless your house of prayer, because of its location on the corner of Chicon Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd …”

OK, first I have to explain the significance of Chicon Street. Though Austin had a reputation as a progressive city, in fact it was deeply divided racially. Interstate 35 (I35) ran north-south through the heart of the city. On the west side of I35 were the centers of power – the state Capitol and the University of Texas, along with downtown businesses. On the east side of I35 was where the minorities lived, forced there through zoning decrees dating back to the 1920s.[1] Growing up as a white teenager in Austin, I was frequently warned never to cross I35 into “East Austin” – the image communicated was of a lawless urban jungle. So far from the truth, as you will see!

For me, Chicon Street represented the Hispanic population of East Austin. I became aware of Chicon in the late 1990s, when there was a March for Jesus that traveled on Chicon through the Hispanic neighborhood. The history of this event is important. In the 1990s, significant efforts were made to unite the pastors of Austin across denominational barriers. The racial barrier, however, proved harder to cross. What happened in one meeting became the stuff of legends. The white pastors were meeting with some of the black pastors to invite them to a pro-life gathering. The response from one of them was: “The only time we see you is when you come invite us to cross I35 for your events.” A young white pastor, relatively new to the city, stood up and said: “I’ll take that challenge!” He and the black pastor began meeting together regularly, became friends, and began to share pulpits.

Out of their friendship, the decision was made to hold the March for Jesus in East Austin, instead of taking the traditional downtown route. I found myself on the “wrong side” of I35, marching down Chicon Street, singing praise to Jesus with thousands of fellow believers. My initial trepidation turned to joy as I walked, and I simply fell in love with the neighborhood. The next year, my wife and I bought a house on the East Side, close to Chicon Street on Canterbury, and moved in with our two young children.

So locating our new ministry Austin House of Prayer (AHOP) on Chicon Street was natural. I knew that most of the intercessors who came would be from white West Austin, and I wanted them to have the same experience I had – overcoming my fears, crossing I35, falling in love with the the whole body of Christ in the city, instead of just one part of it.

Back to Greg’s email, which we can now finish: “God will bless your house of prayer, because of its location on the corner of Chicon Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd, because of my servant J.J. Seabrook.”

What??

Who was J.J. Seabrook? What was his connection to our new location for AHOP?

I had to know, so I called Greg. The story he recounted transfixed me … I was a native Austinite, but this piece of my city’s history was new to me.

In the 1970s, Austin joined the wave of cities across the US naming streets in honor of the late Martin Luther King Jr. In most cities, the “MLK” street or boulevard ran through the black part of town. Austin was unique, because the street that had been voted by the City Council to be renamed was 19th Street – which ran through the black part of East Austin, then crossed over I35 on a bridge and continued on through the heart of downtown, between the university and the Capitol.

On April 3, 1975, the city council voted 6-0 to rename the street on the east side, up to I35. The next week, they took up a proposal to finish renaming the street on the west side of I35, and it passed 4-2, with opposition from a number of white business owners on the West side. Essentially they were saying “It’s alright to rename the street on the East side … but you aren’t renaming our 19th Street.” One of the reasons they gave was the cost of stationery to reprint their business cards and letterhead – which of course elicited cries of racism from the East Side. The battle raged publicly, as recorded by newspaper articles from 1975.

The business owners discovered that while the City Council had voted to rename the street, they had not appropriated the $54,000 necessary to change the street signs. They began to exert their considerable political pressure, lobbying the council members in opposition to the vote for the $54,000. And the tide began to turn.

It came to a head at a city council meeting on May 1, 1975.

A newspaper article described it: “Emotion has been heavy on both sides, and charges of subsurface racism have been levied for weeks. It was in that climate that the council had scheduled another public meeting on the entire matter.” Citizens signed up to speak, and the likely contentious debate was put off until all the other council business had been completed. Then the motion to approve the money for the street signs was put forward. Six argued against appropriating these funds, followed by three in favor. And then a “substitute motion” was proposed to table the vote and bring in the possibility of renaming other streets — which would effectively not only kill the possibility of funding the necessary street signs, but also present the possibility of rolling back the two previous votes for renaming 19th Street. Even worse, a preliminary roll call of the council members showed that the tabling motion would pass 4-2.

And that was the moment that Dr. J.J. Seabrook to come forward to speak on the issue.

Portrait of Dr. J.J. Seabrook

Who was Dr. Seabrook? He was a black pastor and educator who had come to Austin to become the first permanent President of Huston-Tillotson University, a HBCU located in East Austin. He had built up Huston-Tillotson in significant ways before retiring, and in the process had become highly respected by all civic leaders, whether white or black. When he had initially been approached by members of the Austin Black Assembly, who were spearheading the initiative to rename 19th Street, he had resisted. But they convinced him of the symbolic importance of this public battle.

So when Dr. Seabrook came to the podium, the political tide had turned against the renaming and the council meeting was wrapping up.

He began by stating that the City Council had already voted to approve the naming on both sides of I35.

And then, in the midst of his speech, Dr. J.J. Seabrook suddenly collapsed at the podium.

Panic and confusion ensued.

The ambulance arrived and carried him away.

The council meeting was declared over, without holding any final vote.

The city awaited word, which came quickly – Dr. Seabrook was dead.

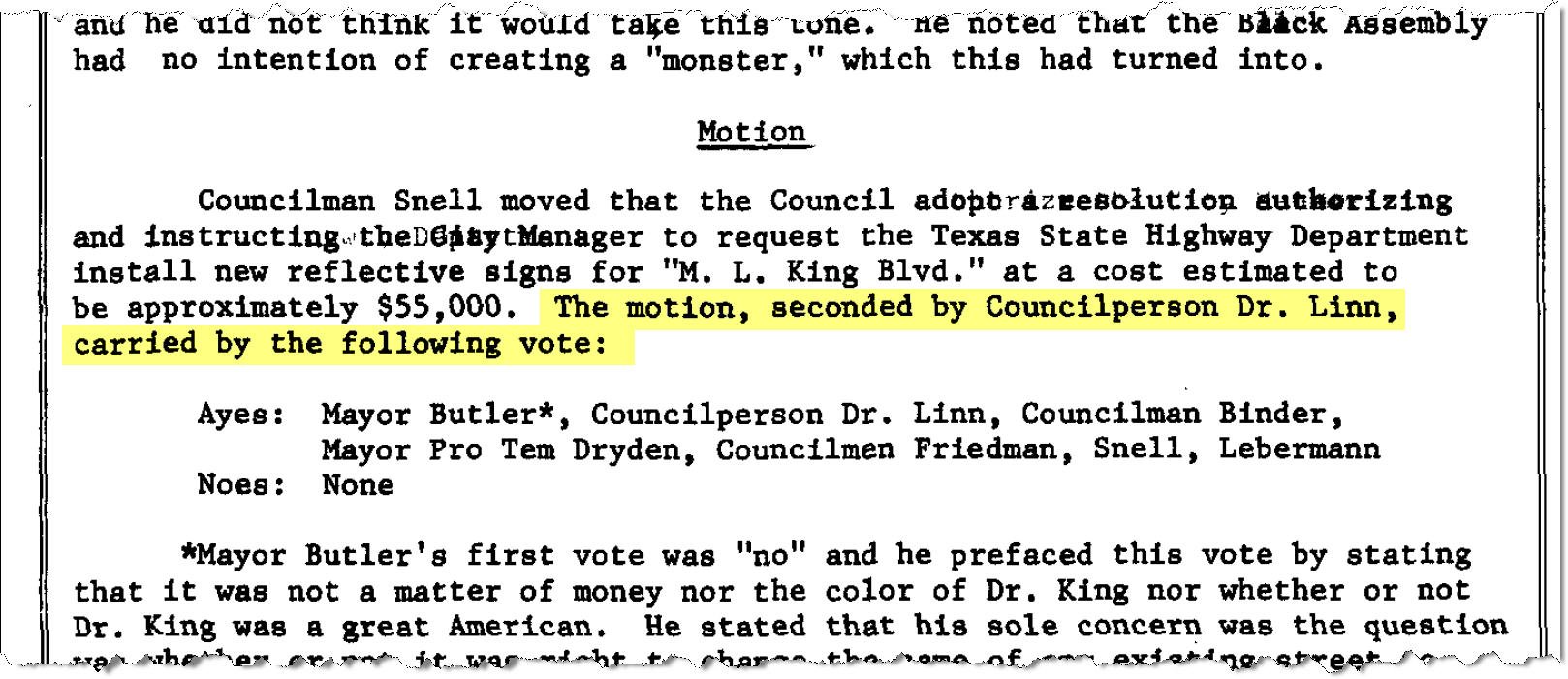

From the Austin City Council minutes for May 1, 1975

Well, when the city council reconvened after his funeral service, they voted unanimously to rename the entire street “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd.” – on both sides of the interstate.

From the Austin City Council minutes for May 6, 1975

“Wow!” I could hardly believe Greg’s story, but immediately thought – “Here is a man who gave his life for the cause of reconciliation!” So, two years later, when we moved AHOP to a dilapidated warehouse farther east on MLK, Jr. Blvd, we decided to name the entire building “The Seabrook Center” in honor of Dr. Seabrook.

The Seabrook Center, 2830 Real Street

We had many visitors come and tour the building, who would inevitably ask, “Why is it called the Seabrook Center?” I would tell them the story that Greg told me, and their reaction was always the same when Dr. Seabrook dropped dead at the podium – shock and amazement.

One night in March 2010, I told the story at a fundraising dinner for AHOP. In attendance was a longtime friend from church named Bob O’Dell. Bob was an entrepreneur helping to lead a technology start-up in west Austin. A couple of days later, I received an email from him – “I believe there may be some spiritual ‘jewels’ in here that can help identify some of the key racial root issues that Austin struggles with.” He had gone into the city council archives and dug up the minutes from the meeting on May 1, 1975. Bob scheduled a meeting with me and said, “We have to bring this story back to the consciousness of the city, so it isn’t forgotten. Let’s have a ‘Remember JJ Seabrook Event’ on May 1 of this year, 35 years to the day after his death.” And then he said the magic words, “If you’ll help me organize it, I’ll pay for it!”

Looking back, it was a true miracle. We had six weeks … and I was in Europe on a business trip for three of them! Bob quickly formed a team to work on the project. The team found and rented a meeting hall on MLK Blvd, on the west side - in a building that in the 1950s had housed the first integrated dormitory for the University of Texas. Frank Costenbader contacted the city council and reached out to find any living descendants. I spread the word among pastors and leaders that I knew. But the key moment was when Frank and I approached Rev. Joseph Parker of David Chapel, a prominent East Austin church.

Reverend Parker sat back in his chair and graciously listened as we told the story. We explained our plans for a “Remember J.J. Seabrook Day,” and concluded with these nervous words: “We realize that the weakness of our plan is that we are white men from West Austin – which is why we’re submitting this idea to you.”

Silence.

Then Rev. Parker spoke, in the beautiful slow cadence that characterizes African-American preaching. He said that what we thought of as a weakness, was actually a strength - because Dr. Seabrook could become a hero for the whole city, not just the East side. He also said that given the short time frame, he felt we were “quixotic”! But he would support the initiative.

Dr. Parker joined the oversight committee. Two other important figures from the east side were also added: Johnnie Dorsey, who had marched with Dr. King, and The Honorable Wilhelmina Delco. Wilhelmina Delco was the first woman and second African-American named speaker pro tempore in the Texas House of Representative. She also happened to have grown up next door to Dr. Seabrook, so she knew him well.

May 1, 2010

So on May 1, 2010 a multi-ethnic, multi-racial, multi-denominational group gathered to Remember J.J. Seabrook. Newspaper reporters were there, and photographers snapped images as speaker after speaker rose to recount their perspective on the story.

Gail Revis, one of two living relatives of Dr. Seabrook, told of being at his house that fateful night, 35 years earlier. The news came of his death, shocking his now-widow and Gail, his niece.[2] Ms. Revis went on to say:

This morning when I woke up, I could almost envision my my aunt and uncle, Opal and J.J. Seabrook looking down from heaven. I could hear my uncle saying, “I now know that my living was not in vain.”

Gail Revis

Bob O’Dell came forward to address the gathering[3]:

Dr. Seabrook died on March 1 and not later because of the opposition from West Austin to the renaming. As a resident of West Austin, I will not run away from this fact. I will, instead, apologize for it. I will apologize today, and I will apologize until everyone who needs to hear it said has heard it said. We in West Austin should not have opposed such an important opportunity to commemorate civil rights in our nation, and we should not have opposed it on the basis of $55,000 for some signs on I-35. IT WAS WRONG. And I speak for many in West Austin when I say, “We are sorry for that, and we ask East Austin to forgive us for this mistake.”

But is appropriate that we do more than just ask for forgiveness. It is appropriate that we do something to make it right. It is my pleasure to announce the creation of a J.J. Seabrook Scholarship Fund at Huston-Tillotson for undergraduate students, with the goal[4] of exceeding the amount of $55,000 that was originally opposed by West Austin.

You can imagine the impact as Dr. Larry Earvin, the current President of Huston-Tillotson, was presented with the honorary check.

Also at the podium that day was the first ever black female Austin City Councilwoman. Cheryl Cole declared that day to officially be Dr. J.J. Seabrook Day across the city of Austin. She also said, “In the next city council meeting, I predict my colleagues will pass a resolution to name the bridge across I35, that bridges east and west on MLK Jr. Blvd – the J.J. Seabrook Bridge!”

And I was in the city council chambers myself two weeks later, as the vote was taken. It was unanimous. I immediately left and drove north to MLK Jr. Blvd., then turned east and crossed over the bridge. I took secret pleasure in knowing that I was the first person to knowingly cross the J.J. Seabrook Bridge.

The bridge, now named for Dr. J.J. Seabrook!

This sign was placed at the bridge, where pedestrians gather on either side waiting for the light to turn so that they can cross. Now, they had something to read while they waited! The text of the sign was composed by Huston-Tillotson students, who had heard about the project and wanted to contribute. They did their own research, and it was significant that they highlighted the crucial contributions of the Austin Black Assembly (ABA). One of the original ABA members, Freddie Dixon, attended the Remember J.J. Seabrook Day ceremony in 2010, and also spoke at the bridge naming ceremony in 2011.

And on January 19 of the next year –– my heart was filled with awe at the back story that led to that moment, as a crowd of thousands re-routed their traditional MLK Day march to celebrate the newly named J.J. Seabrook Bridge by crossing over it and proceeding to Huston-Tillotson University for a dedication ceremony!

January 17, 2011

Bob O’Dell walking with Wilhelmina Delco along Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd towards the bridge naming ceremony in 2011.

There is a beautiful postscript to the story – as if God painted a beautiful painting, then signed it at the end with a flourish. I called Greg Burnett, and told him all that had come of his mysterious email message to me six years earlier. Here is the gist of what Greg said in reply, which made my jaw drop:

Thomas, let me tell you how I came to recognize the importance of Dr. Seabrook’s story. I had come across the story while doing research for a prayer project, and it stayed with me. I left Austin and was living in Charleston, South Carolina. Then one night in the year 2000, I had a dream. I was looking down on Austin from above, with great fondness in my heart for a city I loved. I saw the river, and downtown, and the University … then suddenly, my attention was drawn to the bridge where MLK Blvd crosses I-35, and I saw a massive foot come down directly on the bridge. I heard a thundering voice, clear and powerful. It was definitely the voice of God. He said, “I will bring East and West together!”[5]

So, if you think about it – the dream that God gave Greg about His foot taking a stand on the bridge … led to his email to me about AHOP … led to my naming the Seabrook Center … led to Bob hearing the story … led to the Remember J.J. Seabrook Day … led to Cheryl Cole … led to the Austin City Council naming the very bridge that Greg had seen in the dream! And truly, in a small way, East and West Austin were brought together – showing that God both initiates and responds to unity and prayer!

There are many keys to reconciliation in this story. The work of researchers and historians to uncover the truth … the importance of physically relocating yourself to the place of pain … the willingness to show honor rather than contempt … the submission of ideas and visions to those who have experienced the hostility … identificational repentance … the possibility of meaningful restitution … and the power of symbols.

The bridge is a symbol of division. The renaming of the bridge is a symbol of reconcilation. God loves and uses symbols to speak to humans. But it is important to remember that symbols can become meaningless without true changes in hearts, words, and actions. There is much more work to be done in the area of reconciliation in Austin, in the USA, and in the world. Let this story encourage you that God will be with you as you do this work, and in fact that it is Christ who is the Reconciler … we are just privileged to partner with Him in His work.

Footnotes

[1] See http://www.eastendculturaldistrict.org/cms/gentrification-redevelopment/how-east-austin-became-negro-district for more about this history.

[2] I remember after the ceremony hearing Gail Revis put a remarkable postscript on her testimony. The morning after Dr. Seabrook died, she went with his wife Opal, now his widow, into his study to begin the terrible task that attends every death of “going through his papers.” To their surprise, they found all the legal documents laid out on his desk, in perfect order – as if he had anticipated this moment before he left the house with his speech in hand.

[3] Some of this speech is abridged / paraphrased for the sake of brevity.

[4] The goal of $55,000 was met shortly after the event, which made it an endowed scholarship that exists to this day.

[5] This comes from Bob O’Dell’s wonderful book, Five Years with Orthodox Jews. He gives his perspective on the J.J. Seabrook initiative in Chapter 35, “A View Too Small – First Steps.” I had remembered Greg telling me a slightly different message from the voice in the dream, but Bob called Greg and asked him what he had heard, which was the message about East and West being brought together.